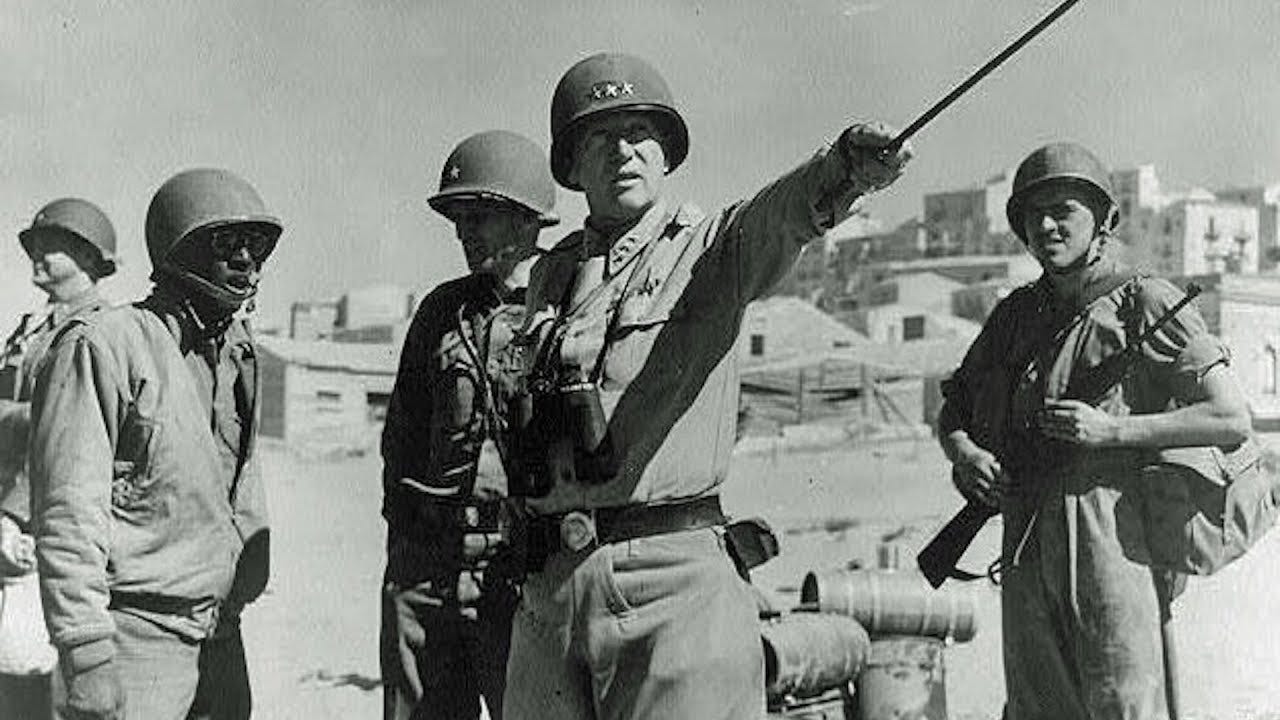

(I aspire to “do better” on headline-writing, but sometimes a cliché is all you need. In my effort to “class up” the reference, I discovered the title of the video game franchise was inspired by the photo above from 1954)

How fast should you go when developing a new product, or making an improvement to an existing one?

This seems like a simple question, but is a surprisingly contentious one in large, and/or complex product teams. Of course no one in today’s corporate America will argue for “going slower”. “Innovation”, “evolution”, “change is inevitable”, and all that jazz, dominate the spoken culture of these organizations. But people argue all the time for “getting more data”, “let’s be sure customers want it”, “let’s go deeper” during the inception phase of a product. Similarly during execution, you’ll hear “we need to build it right”, “we can’t accumulate tech debt”, and “we are running too hot”. So, no one argues for “going slower”, but many people argue for going slower. They just use different words.

Of course, like all good ones, the arguments for going slower have merit. You don’t want to ship an undependable product, or kill your development team to hit an unrealistic timeline. But I’ll contend that, as good as these arguments usually are, interpreting them to go slower is almost always a mistake.

There is One Optimal Development Speed: Fast

To get the answer of the question above out of the way: you should always go fast. As fast as conceivably possible.

But, it is an easy statement to make. Especially for a product manager, a marketing manager, a CEO, a designer, etc. Basically anyone who is not actively coding the product, or have to deal with the operations of it after launch (people who don’t get paged in the middle of the night when something breaks). It comes across as idealistic or naïve. But I’d still argue: I don’t care; you should go fast.

Go fast in this context doesn’t refer to how much, the team is working. But rather to how quickly you can get the product in the hands of a customer. Those two things seem to be related, but they are at odds most of the time.

To use a simplistic example: a team writing a program that is 100 thousand lines of code (LOC), at the rate of 1000 LOCs a day, will be ready to ship a program to the customer in 100 days. On the other hand, a team writing a program of 40 thousand LOCs at the rate of 800 LOCs a day, will be ready to ship in 50 days, while working less every day.

Moreover, the 100K program will probably require more QA and testing, and have more bugs than the smaller program, further slowing down delivery to the customer. And chances are that to hit the higher rate of output, the team working on the bigger program had more individuals (or sub-teams) working in parallel, increasing the chances of miscoordination, and “interface-drift” creating more avoidable mistakes that further slow down delivery. This may seem counterintuitive, but harder working teams are liable to ship slower.

We will come back later to whether the 40k program is equivalent to the 100k one. That seems like a big logical jump. But let’s first address why is it so important to go out to the customer in 50 days, rather than 100 days.

Shooting at Moving Targets

Ben Evans has this expression of how some product companies (in that case, Facebook) are good at “surfing” customer behavior. That refers to their ability to respond to customer behavior as it emerges. For example, Snapchat introduced stories, and once Facebook recognized that customers like the feature, they were able to ride the wave and introduce stories in Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. In this case, it is obvious that having some degree of agility was important for Facebook to catch up before enough people were locked into the Snapchat network. Facebook’s ability to execute Snapchat’s strategy faster than Snapchat itself, ultimately helped cement their place in the front.

But even in cases that are not that obviously competitive, there are reasons why you want to be able to execute quickly, and it has to do with the fact that your customer behaviors and preference are not static. They change all the time. Sometimes independently - due to bigger trends in the world - but most of the time due to what your products, and alternative ones train them for. The longer you spend between product inception and delivery, the more likely customer behavior has moved on from what you initially targeted or assumed.

My favorite example is from early in the development of Amazon Business. Amazon was new to the B2B space, and not knowing better, we looked around at the B2B industry and interviewed a lot of customers to understand what problems we can solve for them. One problem that seemed obvious is the need of customers to order and fulfill orders in bulk. One research university we talked to told us how they order two trailer trucks full of printing paper every week, and that for us to be competitive we need to be able to fulfill that kind of demand, and comply with all their delivery requirements (specific delivery windows, truck permits, access codes, etc.). Given that this was the antithesis of what Amazon was built to do (break down orders and deliver them as quickly as possible), my team spent a lot of time working with relevant teams to build bulk fulfillment capabilities, add additional order information, change planning algorithms, etc. After few long months, we were ready to launch a proof of concept with that specific university.

To our surprise, we didn’t see any bulk orders come in. We were doing well, and the number of orders coming from the university was growing, but we didn’t see any trailer-truck orders of paper. It was perplexing. Rather we were seeing small orders of 1-2 reams of paper coming from a large set of users. When we reached to the purchasing team at the university to understand what happened, they started by explaining how the admin community was excited about the decision to onboard with Amazon, and how they created an account for the admin assistant in each department, so that they can shop for their supplies, the way they shop on Amazon for personal use. An admin assistant explained enthusiastically “this makes so much more sense. Why do I have to send orders to purchasing and wait for them to fulfill it in bulk, when I can order onesie, twosie whenever I need it, like I order at home from Amazon”.

In other words, we had the right product for this customer a few months earlier than we thought. We had the 40k LOCs program (in this case, closer to 0k), but we spent the time building the 100k solution. Had we known that, we could have spent the time building features that are more useful to that customer, or focused on building the bulk fulfillment capabilities for customers who show us that they absolutely need it (by trying and failing to use the base product). Of course, we were lucky in this example. The customers liked what we were good at. But it could have easily went a different way, and by the time we built a product to the customers’ stated preference, someone else would have built another product that altered their preference, and we would have had to chase.

The risk of showing up too early is knowing that you have to do more work. The risk of showing up too late is having to throw away all the work you have done.

Patton vs. The Planners1

The most interesting aspect of the dynamic described above, was that our presence in that market was changing the stated preference of customers in real time. We were not just walking into an unexplored field. Rather, our mere presence there was changing the field itself. There was no way for us to know what the field will look like, without actually getting there.

So why don’t we all get there fast? Why do we feel the need to build fuller products first (the 100k program), when a smaller, more minimal product could be enough to start with?2

I think this comes from a confusion about the concept of “planning”. Most large organizations consider “planning” a central part of what they do. When it comes to building product, “planning” looks like asking a lot of questions about the strategic reason for building the product, conducting customer research and interviews to make sure we are building the “right” product, and building a lot of financial models and projections.

It is equivalent to generals pouring over maps, building scenarios and fallback measures, and projecting every potential opponent move, and planning for how to counter it, ahead of battle.

In both cases, generals and managers are trying to anticipate what the field will look like, not recognizing that - essentially - there is no way to anticipate the filed without being in the field.

The most successful general in history - Napoleon - seems to have instinctively understood that. In describing von Clausewitz interpretation of Napoleon’s strategy in his first major Italian campaign, Bill Duggan relates3:

The Italians and Austrians identified Milan and Turin as strategic objectives. So that was where they concentrated their forces. But Napoleon had no strategic objectives. Instead, he set his army in motion with no definite destination, and then looked for opportunities where he could win a battle. The place and time were completely unpredictable, and he passed on more battles than he fought.

That seems like one person’s interpretation of the military genius. But Napoleon confirmed that in his own writing:

I had a few really definite ideas, and the reason for this was that instead of obstinately seeking to control circumstances, I obeyed them.. Thus it happened that most of the time, to tell the truth, I had no definite plans, but only projects.

This seems counterintuitive. Doing anything sufficiently meaningful today, especially in high tech products, require a lot of thought, and, well, planning. How do you reconcile that with just “setting the army in motion” and seeing what happens?

The synthesis of that tension comes from General George Patton, who was arguably the most successful allied general of WWII, and who was a student of both Napoleon and von Clausewitz’s interpretation of his military thought. He was obsessed with speed, and keeping the army in motion like Napoleon. He declared in his famous speech to the 3rd Army that “I don't want any messages saying 'I'm holding my position.' We're not holding a goddamned thing. We're advancing constantly and we're not interested in holding anything except the enemy.” That put him in constant conflict with his superiors who valued meticulous planning ahead of battles. Omar Bradley, the General of the Army, admired Patton’s achievements and results, but continued to favor other generals who displayed more traditional ability for battle planning.

In explaining that apparent dissonance, Duggen hypothesize:

No [, Bradley was not contradicting himself]. He meant that Patton can not be bothered with details before making a decision. After Patton made a decision, he worked everything in great detail, in true von Clausewitz style. Hodges and Bradley like true […] planners, worked out all the details beforehand - they thought that was how you made decisions in the first place.

In other words, maybe the solution out of the conflict between speed and complexity is that you need planning. But planning that done after you step on the field, understand the terrain, identify opportunities and how to quickly capture them. In building product, you are only truly “on the field” when the customer has the product in their hands. That’s when the interviews, research and projections matter. Because they are built on a kernel of truth about the customer and their evolving reality.

Everything that happens before that is elegant guessing.

This title is the title of the chapter on General Patton from William Duggan’s excellent “Napoleon’s Glance: The Secret of Strategy”, the book that first introduced me to Patton, and more generally Clausewitzian strategic thinking.

There is a lot that has been written over the years about the Lean Startup methodology, and the importance of building Minimally Viable Products (MVPs). I don’t disagree with most of this. My intention here is to unpack the “planning” mental model that invariably leads people who know about MVPs and LS to still go slow.

Ibid.

Great Article! Thank you Wael